Most people under the age of 40 have little to no knowledge of the St. Adolphe ferry and how critical it was to the town’s residents. It was used by almost every family in town on a daily or weekly basis.

Ferries were once a common means of crossing the Red, Assiniboine, and many smaller rivers in the province, but they gradually disappeared as bridges were built to provide faster and more convenient access.

In St. Adolphe, one needs to look beyond the so-called rubble, which is no longer displayed in public after it was vandalized 10 years ago, to recognize and appreciate that the ferry—also known as Watercraft #313869, registered to the Port of Winnipeg—is one of the most important icons of the town’s heritage. Our past, if we don’t take the time to understand and preserve it, can be like a foreign country.

The ferry has a story.

Home on the River

The St. Adolphe ferry was established in 1893, two years following the incorporation of the Rural Municipality of Ritchot, at a time when the settlement was known to many as The Royal Crossing, or Pointe Coupée. The ferry was one of eight operating in the Red River Valley between Emerson and Winnipeg, the other crossings occurring at Emerson, Letellier, St. Jean Baptiste, Morris, Aubigny, Ste Agathe (since 1882), and St. Norbert.

The ferry connected Provincial Road 429 to Highway 75 on the west side of the river. Provincial Road 429 doesn’t exist anymore, but we know it as Taché Avenue in St. Adolphe. It used to have houses situated along it belonging to the Gagnons, the Lagassés, Mr. Levesque, and the Bouchards.

The ferry made the crossing several times a day and was used to transport children to school and back home again. It brought mothers to shop and fathers to work. It transported horses, oxen, and later cars and trucks, back and forth, day and night. It was used by the Filles de la Croix, the nuns of the St. Adolphe Convent, on a regular basis, especially when they took their daily walks with the boarders up to Highway 75.

Physical Structure

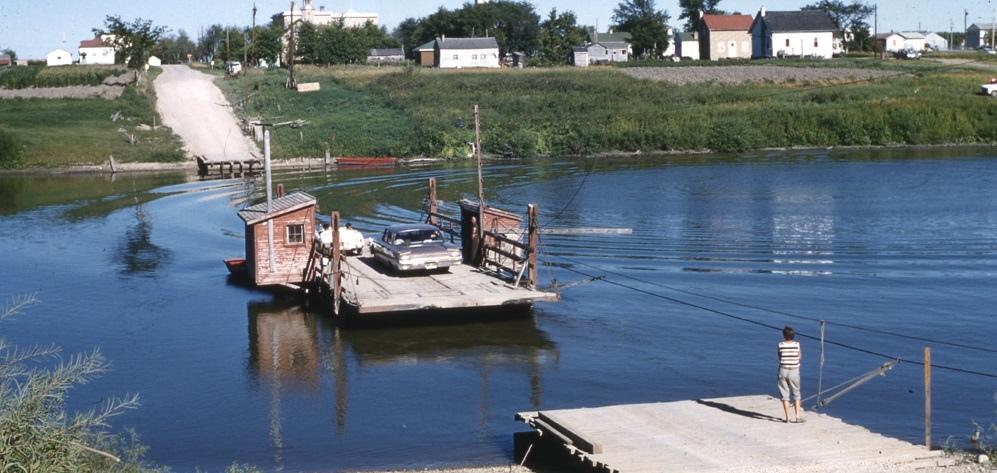

The St. Adolphe ferry was a barge with steel beams. It had a solid plank floor that was three inches thick and was maintained annually with tar on top to seal the cracks. Constructed in Winnipeg, it was 54 feet long, 25 feet wide, and weighed 31.96 tons. The ferry aprons, connected to each side of the ferry, were built with 2-by-12 boards attached to a frame and provided a landing dock. Operators needed to ensure that there was always two feet of water between the ferry’s edge and the shoreline before the apron could lower into place.

Prior to the vessel being powered, the ferry was operated by manpower alone—with elbow grease and heavy ropes. In the 1940s, two small wooden huts were built on either side of the vessel. One served as the ferry operator’s quarters and it contained a little bunk, a hot plate, and a radio. It was also crammed with 26 life jackets, fire extinguishers, chains, boots, and an emergency pump. The other hut, the pilothouse, was filled with machinery, the transmission of a one-ton truck and a flywheel that wound the ferry along its cable endlessly back and forth. It was powered by a five-horsepower motor, and every time it stopped it was tied to a post.

The ferry could carry four to six cars, but farm equipment and trucks were ferried across the river on separate trips. Drivers and passengers often emerged from their cabs to talk to the ferry operators, and in turn the ferry operators liked to explain the machinery workings inside the dark pilothouse.

Wind sometimes proved to be a challenge—south winds, in particular. These winds would pull the ferry downstream, causing the cable to tighten, and make landings more difficult.

The Ferry Operators

The ferry provided plenty of employment for locals, since operators were required to be on hand 24 hours a day, seven days a week for the eight months per year it was in operation.

One local ferry operator, André Chaput, born November 12, 1925, was employed by the RM from May 1946 until November 1950. He started working at the end of April when the water level was low enough for them to attach the cables and start transporting people.

Chaput recounted stories of sleeping on the ferry. If he was asleep, folks waiting on the shoreline would ring a bell to awaken him. If he wanted a day off, he had to ask Lévi Courchaine to relieve him of his post.

The municipality provided a ferryman’s house, and Chaput’s wife and children lived there for four years. He walked back to the house for meals, or his children would bring food to him. The foundation of the ferry operator’s house is still intact on private land.

In 1946, Chaput earned $90 a month, which might not seem like much, but his lodgings were provided for. In 1951, he asked for an increase to $110, but the RM instead hired Harold Carriere, who worked as the ferry operator from 1951 until 1962.

In October 1962, a fully loaded gravel truck pulled onto the ferry. Carriere started the crossing and the ferry pulled away from shore, but the weight was too great, and it sank not far out. Carriere drowned despite the truck driver’s efforts to rescue him from the icy waters.

The ferry sank but was pulled out of the river following the accident.

Emmanual Nolette, born and raised in Ste Agathe, operated the St. Adolphe ferry from 1962 until 1976. He was raised on the banks of the Red River and was proud of his work as a longtime ferry operator. He once said, “On the river, I have everything that I need.”1

Nolette had lost his three-year job as ferryman on the Ste. Agathe ferry when, for economic reasons, it was replaced by a new $450,000 bridge on November 7, 1960. He had fond memories of the people of St. Adolphe, a town of 400, bringing him chickens, homemade bread, and fruit.

When Nolette needed a break, Zotique Delorme was hired to operate the ferry and was paid $1.85 an hour and time plus one half after 44 hours.

Philias Paul Lagassé of St. Adolphe, a municipal worker, also lost his life onsite. On March 20, 1970, Lagassé was operating a tractor at the river’s edge to clear snow around the ferry in preparation for the new season. After all, every winter the ferry sat locked in ice. As the water flowed under the frozen ferry, an eddy formed on the north side, where the ice was always thinner. In a tragic turn, the tractor broke through the ice and sank. Lagassé drowned.

The Red’s Last Ferryboat

From 1948 to 1971, residents of the RM were entitled to unlimited rides free of charge while others were charged 15 cents for a car, motorcycle, bike, or horse. After 11:00 p.m., a one-way trip cost 15 cents. If you had to wake the ferry operator between 2:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m., it cost a steep sum of 25 cents. Semi-trailers were charged a 50-cent toll.

As St. Adolphe grew in size and commerce, the ferry became a convenience for the townspeople who worked in Winnipeg and commuted along Highway 75. It was used by neighbouring farmers from the east side of the river who did business in St. Adolphe, and it was often used to carry local trucks full of sugar beets across the river so they could bring their loads to the Manitoba Sugar Beet Factory in Winnipeg.

Ben Wiebe of Steinbach remembers taking the ferry in 1958–59, when he was 16 years old, “to drive a sugar beet truck with a heavy load—around six to seven tonnes—plus the truck, that was 20,000 pounds, over to Brodeur Brothers, and then follow north along Highway 200.”

The ferry was a tourist attraction for weekend drivers when they crossed the river to visit the St. Adolphe Park, picnic grounds, and campground.

“I get visitors from all over the world,” Emmanual Nolette once said, “and I don’t know how many pictures have been taken of us.”2

Ironically, in 1962, the ferry itself was seen as an obstacle on the Red River south of Winnipeg. The Red River was marketed to city folks as navigable for those wanting to take weekend cruises from Winnipeg to the United States. The obstacle lay in the fact that ferry cables were stretched across the river. Visitors needed to phone ahead so the ferry operator knew to lower the cables to the bottom of the river, which was only possible if the conditions were favourable and the water wasn’t too high.3

By 1969, the St. Adolphe ferry was the only surviving ferryboat on the Red River, providing a shortcut across the river, an alternative to driving to another crossing either south at the Ste. Agathe bridge or north at the South Perimeter by St. Norbert.

Following Harold Carriere’s tragic accident in 1962, the ferryboat itself was replaced by the one that had been operating in Ste. Agathe before the construction of the bridge there. That boat had been built new in 1954.

The province officially took over responsibility for the St. Adolphe ferry in 1965. The province, in turn, paid the municipality an annual sum of $9,000 to cover its operational expenses. Other ferries operated directly by Manitoba’s Department of Transportation included the Winnipeg River ferry and the ferry crossing Lake Winnipeg to provide access to Hecla Island.

By the late 1960s, the RM of Ritchot requested that the ferry be replaced by a bridge, despite the municipality feeling proud to be the custodian of the last Red River ferry. Low traffic counts on the ferry made it hard to justify the estimated $500,000 needed to build a bridge, but the fact remained that the current ferry was aging and in need of repair. Local residents needed a faster and more efficient means of getting across the river.

In the spring of 1972, the RM of Ritchot passed a resolution to dispense with the practice of collecting a toll from people who weren’t residents of the municipality. Ritchot also passed a resolution requesting that they receive $14,000 per year from the province to operate the ferry, since the annual costs had by this point exceeded the $9,000 they had been receiving.

When the St. Adolphe ferry was drydocked in the fall of 1972, the hull was rotted and pitted. The federal Department of Transport in Ottawa, which issued the yearly license to operate the ferry, stated that “a brand-new hull was necessary if it was to run again.”4

Since the bridge was still too expensive a solution, repairs were undertaken. These repairs met Ottawa’s standards, and so another operating license was issued for 1973.

However, the provincial government decided in late 1973 to withhold approval of new bridges in St. Vital and Fort Garry, forging ahead instead with a permanent bridge at St. Adolphe. It has been said that the bridge was high on the list of campaign promises made by MLA René Toupin, who after the 1973 Manitoba General Election was named the Minister of Tourism.

This decision was met with relief and excitement from Ritchot’s council since they and local residents had become concerned over changing water levels that sometimes led to the ferry running only intermittently in the middle of summer. They also considered the ferry’s history of operational challenges and its age, despite the previous year’s repairs.

Crews had already begun the steelwork for the St. Adolphe crossing by the time the provincial government made the announcement public. The government was accused of building “a bridge that leads from nowhere to nowhere” and “of dropping the equivalent of the Golden Gate Bridge into the agrarian community of St. Adolphe.”5 It was also noted that “there were excellent bridges seven miles each side of St. Adolphe” and that “St. Adolphe was a community completely surrounded by a ring dike and shows no signs of growth.”6

Despite opposition, the provincial treasury committed to the project and bore the full cost of what is now known as the Pierre Delorme Bridge. The original Pierre Delorme Bridge was replaced in 2011 after an incident on August 21, 2009. On that day, a pier supporting the structure sunk three metres and caused the deck to buckle.

More Than Rubble

In the fall of 1976, the St. Adolphe ferry was pulled out of the Red River for the last time and placed on blocks at the side of former crossing. The St. Adolphe Chamber of Commerce expressed interested in displaying the ferry in St. Adolphe Park, but the idea wasn’t pursued.

In 1986, the ferry was moved to a parcel of land on Main Street, across from the Catholic Church, owned by the province and managed by the municipality. It was restored by volunteers and showcased as a tourist attraction. The Crow Wing Trail Association installed interpretive plaques beside the ferry to tell its story as a prominent piece of history.

Unfortunately, the ferry was substantially vandalized in 2009 and was moved offsite in 2015.

Today, all that’s left of the St. Adolphe ferry sits protected in the RM of Ritchot’s Public Works yard. The ferry’s future is unknown, and its potential as an attraction has yet to be realized.

It’s more than just a pile of rubble; it’s an icon. The St. Adolphe ferry connected and served the community for 82 years and many residents today still remember riding it. The operators and their families dedicated years of service to provide safe crossings.

Watercraft #313869 is a valuable heritage asset for the growing community of St. Adolphe. In this day and age, when we have grown increasingly distant from our individual and collective heritage, we all seek authentic connections to times past.

Perhaps this story can remind us of our past, so that it doesn’t become foreign to us—for our children, and for the generations that follow.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

1 Peter Michaelson, “He Skippers the Last Ferry on the Red River,” Winnipeg Free Press. September 11, 1971.

2 Betty Campbell, “Pride and a Sense of History,” Winnipeg Free Press. May 19, 1973.

3 “Red River Now Navigable But Phone Before Cruising,” Winnipeg Free Press, July 14, 1962.

4 Campbell, Winnipeg Free Press. May 19, 1973.

5 Fred Cleverlty, “Commentary,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 6, 1975.

6 Ibid.